---

title: "How to fix (model) sensitivity problems"

author: "Matthew Wilon"

date: "2025-09-29"

format:

html:

code-fold: true

toc: true

---

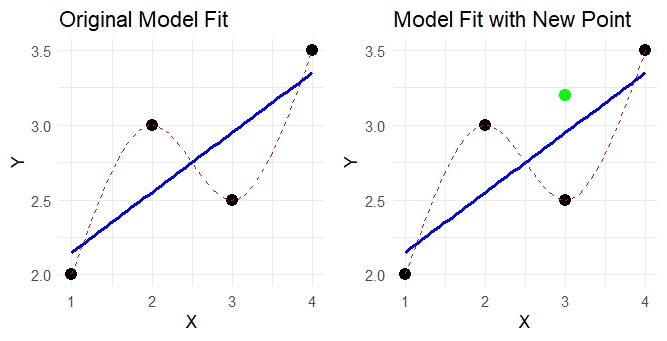

When learning to build statistical models, the moment the model “fits” the data and your assumptions are met you tend to pat yourself on the back and call it a day. But in the *wild*, models need to be [flexible](#flexibility). They need to fit not just the data present, but future data. We need to make predictions with this model. We will consider how model sensitivity relates to these flexibility.

## Flexibility

Lets consider these two models. Both of them predict the data. Both of them accuratly model the data, but how well will they model another data point from the same sample? p.s. The code is provided in case you would like to experiment with this youself.

```{R, warning = FALSE, eval = FALSE}

# This code was produced with the aid of Microsoft copilot

library(ggplot2)

library(splines)

library(gridExtra)

# Original data

df <- data.frame(x = c(1, 2, 3, 4), y = c(2, 3, 2.5, 3.5))

# Spline data

spline_df <- data.frame(x = seq(1, 4, length.out = 100))

spline_df$y <- predict(smooth.spline(df$x, df$y, df = 4), spline_df$x)$y

# First plot: original model fit

p1 <- ggplot(df, aes(x, y)) +

geom_point(color = "black", size = 3) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, color = "blue", formula = y ~ x) +

geom_line(data = spline_df, aes(x, y), color = "red", linetype = "dashed") +

labs(title = "Original Model Fit", x = "X", y = "Y") +

theme_minimal()

# Second plot: with new point

df_new_point <- data.frame(x = 3, y = 3.2)

p2 <- ggplot(df, aes(x, y)) +

geom_point(color = "black", size = 3) +

geom_point(data = df_new_point, aes(x, y), color = "green", size = 3) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, color = "blue", formula = y ~ x) +

geom_line(data = spline_df, aes(x, y), color = "red", linetype = "dashed") +

labs(title = "Model Fit with New Point", x = "X", y = "Y") +

theme_minimal()

# Display side by side

grid.arrange(p1, p2, ncol = 2)

```

Although the dotted line appeared to be an exceptional model for the data collected, it doesn't adequately model the whole population. Some model diagnostics will not catch overfitting, and might even tell you that it is an amazing model. In the above example the $\text{MSE} = 0$. Which would be amazing. The problem is that this model isn't flexible enough to accuratly predict future observations, nor to provide correct confidence intervals. It is *overfitted* to the data. We need a model that is more flexible to handle variance in the data.

### Problems

Let's discuss a couple potential problems leading to overfitting.

+ [Too many predictors](#predictors)

+ [Multicollinearity](#multicolliniarity)

#### Predictors

In a world saturated with data, sometimes **less is more**. Especially when it comes to the number of predictors we use. As data scientists, we're presensted with all the data collected. It is up to us to sift through the information available and to select the variables that are necessary to answer our questions. If we have to many predictor variables in our model we run the risk of finding significance that isn't there. For example, if we are testing significance with $\alpha \le 0.05$ and we test 20 insignificant variables. On average, one of those variables will appear to be statistically significant even though in reality it isn't. [Here's](https://www.explainxkcd.com/wiki/index.php/882:_Significant) a comic about that if you're interested. When we use to many variables we can create a model where the coefficients tied to our variables match the current data set well, but will not match future data. We can sometimes even "take" some of the relationship from one variable and "give" it to another if the two variables are related. This is related to multicollinearity.

#### Multicollinearity

One of my first realizations about multicollinearity is that I want to say this word as infrequently as possible. Luckily this is written and not a presentation. To understand multicollinearity, we must first understand that sometimes predictive variables can be related. For example, if I had a person intereted in contracting me to do data analytics for them and I wanted to determine how much I thought they'd be willing to pay me, I could consider both their income level and their house property value as predictors for the money they'd pay. The problem is that these two variables are often very related. Considering this mathematically, we see that the following equations are equivalent.

$$

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\text{Assume House} &\text{Property Value} = 3*\text{Income } \\

\text{Money Paid}_1 &= (\text{Property Value} - \text{Income})/1000 \\

\text{Money Paid}_2 &= (4 \cdot \text{Property Value} - 10 \cdot \text{Income})/1000 \\

\text{Let Property Value} &= 300000 \text{, Income} = 100000\\

\text{Money Paid}_1 &= (300000 - 100000)/1000 = 200 \\

\text{Money Paid}_2 &= (4 \cdot 300000 - 10 \cdot 100000)/1000 = 200 \\

\end{split}

\end{align}

$$

We can see that, these 2 equations will produce the same results for a prediction of how much money a person will be willing to pay. This is due to a preexisting relationship between income level and house property value. So in this case, if your model were either of these is would produce the right value. The problem is that one of these equations will produce much different values if there is a slight change in Income or Property value. Since in the "wild" this relationship would often be a correlation and not an exact 3-1 relationship. This means that when making predictions for new data points, or in other words a new customer, your predictions could change rapidly despite small differences between them and an existing customer used to train the model. These 2 variables represent multicollinearity. In situations like these, it is generally better to only use one of your variables to include in the model.

### Potential Fixes

It is clear that these issues can be probematic. Today we will discuss two tools that can be used to help mitigate the chance of these problems. It is important to note that although these tools help, it is important to combine them with critical thinking and a personal understanding of your data set and modeling goals. These methods will help you to select potential models to use and to compare different potential models. I will give you enough information about these techniques to get started and to understand their potential. They are honestly interesting enough to have their own blog posts, so I will just focus on gerneal understanding here.

+ [Regularization Methods](#regularization-methods)

+ [Cross Validation](#cross-validation)

#### Regularization Methods

Regularization methods help us to shrink our coefficents to avoid inflated coefficients that increase the variablility induced by slight changes in the data. This can avoid the issue demonstrated in the [multicollinearity](#multicollinearity) example. These methods penalize large coefficients and help "push" them towards 0. Two examples of these techniques are **Ridge and Lasso regression**.

**Ridge Regression** - This is the method to choose when we don't want to elimiate any variables, and just want to keep their coefficents low. For example, if we are trying to predict an animal's lifespan based on water pollution. Two pollutants might be related to each other, but the environmental scientists might want to keep both pollutants in the model. This method helps to find that balance.

**Lasso Regression** - This is called a variable selection technique, since can actually cause a variable's coefficient to be 0, thus eliminating the variable from the model. It, like Ridge regression, includes a penalty that "pushes" the coefficients toward 0. It can aid in both reducing inflation in variables and selecting variables to use.

Both of these techniques can be used to help us as we combine the information they provide with our understanding of the problem. Many coding languages even include functions or packages that will help you use these tools!

#### Cross Validation

Cross validation is an essential aspect to model building. The purpose of cross validation is to check and see how well your model can predict future data. This is essential as a data scientist and a key to ensure that our model is not overfit to our data i.e. unflexible. For cross validation you will select the model you want to use, I would honestly recommend selecting multiple potential models here. You will then randomly split your data up into a *training set* and a *test set*. The model(s) will then be fit to the training set and then tested to see how well they model the test set. If it doesn't do a good job predicting the test set, it is possible that the model is overfitting to your data. You should randomly split up the data multiple times and perform this process to then see how the model fits overall. I believe cross validation should be done everytime a model is being trained.

## Conclusion

These two methods can even be combined and both used in the process of model selection and training. They will help us as data scientists to provide flexible yet accurate models to answer our questions and provide key insights to the problems presented to us. I implore you to check and ensure that your model is flexible and can handle the future data that will be given to it.